Chris emailed to ask:

Dear Mike, Drawing with graphite pencil gives me a lot of pleasure and happiness. In the past using color made me more and more feel like I was losing contact with my work and the pleasure disappeared. But since I removed color from my drawings people keep saying: “Why don’t you use color? You have to use color, that’s much more beautiful” and so on. Probably you have had these comments too. Could you please give me any advice what to say to these people so they stop nagging?

Leaning against one wall of my studio are two pristine stretched canvasses. One drawer of the unit containing my drawing materials is full of unused oil paints, palette knives and brushes. They’ve been there for fifteen years, awaiting the day I feel the urge to paint.

That they are there is a result of my dealers telling me I’d sell more work if I painted. However, I believe they mean they better understand, and can more easily sell, paintings.

One drawer above holds acrylic paints. I once spent half a day using those and thoroughly enjoyed it – but I too felt a loss of connection with the work. I don’t paint. It’s not the way I see the world. I see and enjoy colour but prefer to look beyond and behind. It’s an attractive veneer that hides the real world – the tactile world I prefer to inhabit.

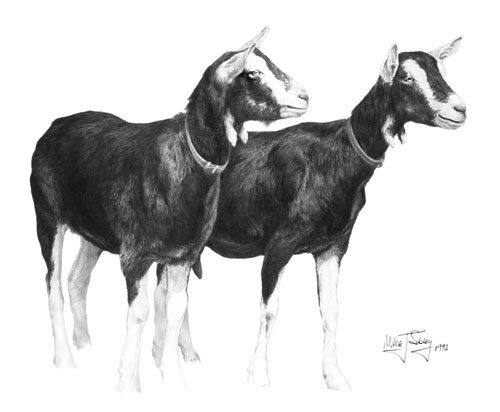

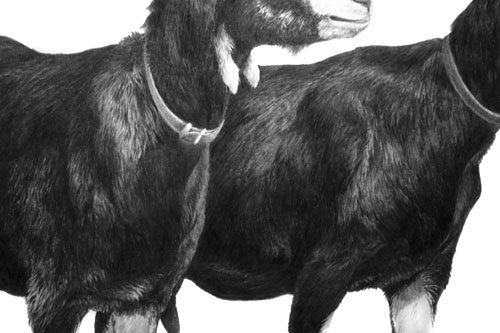

Pencil does everything that I ask of it. I am not a fan of colour. I believe the lack of colour in pencil work forces the eye to look deeper into the image. The eye can scan over a painting and quickly pick up sufficient information to satisfy it just from the shapes, tones and hues of the colour alone.

Pencil, by stripping away the familiar outer covering, demands a much closer inspection. In short, colour can get in the way of real perception.

There’s another important difference between painting and graphite pencil drawing too – spontaneous creation. I think this explains your “losing contact” with your work.

Consider the following:

- We graphite artists only have two “colours” at our disposal – texture and contrast

- We work with a thin, pointed stylus so we tend to become detail orientated.

- By controlling the pressure applied to that stylus we can control the value it produces

- The use of a chisel point means we can switch between a broad face and sharp edge by simply rotating the pencil

Combine those points and they add up to a medium that offers instant and spontaneous creativity.

At this point I should mention that, in my opinion, there are subjects that demand the use of colour and are therefore not suitable candidates for monochrome rendering in pencil. A sunset was my first obvious thought. My next was brightly coloured fishing boats under a Mediterranean sky – but then I realised that’s not true. In fact, pencil would be ideal for that subject. Why? Because almost all viewers will see only the colour. Remove the colour and they are forced to look at the boats – the chipped and peeling paintwork, the old frayed ropes, the sinuous weave of old wickerwork creels… all the textures previously hiding behind colour. The essence of the boats exposed; not just their superficial appearance.

Of course the two elicit completely different reactions – both equally valid. The first generates feelings of warmth and beauty. The second exposes the viewer to the intricacies and beauty of the real world beneath.

Personally I begin each drawing with a set of guidelines within which I work. I then draw one small section at a time. And I rarely return to that section – it is complete and, because I don’t work on it again, it remains sharp and fresh.

It’s the immediacy offered by pencil that attracts me to it. My thoughts travel down my arm, and my pencil translates them into drawing. There are no colours to mix, no drying times, no complex layers to apply. Nothing breaks my concentration. I can create and complete an area in a single unbroken session. I become deeply immersed in it. The work exists in my mind – I can see it; it’s alive – and it’s transferred effortlessly to my paper. I often become so engrossed, and disconnected from the world around me, that it is not uncommon for me to look at the work I’ve just produced and to have difficulty in believing I drew it.

Finally, have you noticed that most “high art” photographs employ black and white film? Again, I’m certain that’s because the viewer is forced to look directly at the beauty of the subject. Composition, balance, contrast, emotion, texture; all are now fully exposed – they occupy primary positions, no longer secondary to colour.

The viewers of our work live in a world of colour and expect to see colour in images. When someone says “You have to use colour, that’s much more beautiful” I think they are really saying “Make my life easier. Don’t make me work to gain enjoyment.” By removing colour we are forcing them to look deeper for understanding, but if they accept the challenge, I believe their enjoyment will be much enhanced. And that necessity to look in depth gives us the ideal opportunity to draw them into the work.

Personally, I try to subtly exaggerate texture, and emphasise contrast – as if to say, “Do you see this? Do you really see this? Isn’t it beautiful, this marvel of Nature.” And if I feel just one person has finally been encouraged to “see” instead of look, I’ll have done my job.